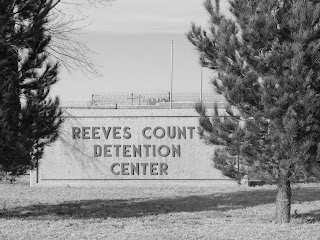

(The first of a series of articles on the Reeves County Detention Center in Pecos, Texas. The articles follow up my Death In Texas article in the Boston Review in November 2009.)

Pecos knows about economic ups and downs.

Abandonment and desolation prevail in this part of West Texas.

Hawks sit atop long-emptied cotton warehouses whose sheet-metal walls moan and clack in the winds that sweep sacross the high prairie. Cotton was once king here. So, too, were cattle drives, oil and gas drilling, and the railroad.

The railroad runs through the center of town, but the Texas & Pacific Railway Station was boarded up long ago, and the trains that pass through Pecos just whistles past, leaving echoes of howling coyotes.

Since the early 1980s Pecos (seat of vast Reeves County) hasn’t experienced any major upswings. Occasional mini-booms fueled by spikes in energy prices have filled the county courthouse with agents of oil and gas speculators looking for cheap properties with possible energy reserves.

But there is scant hope that the glory days of past booms will return to Pecos. Keeping the town alive is the best that anyone here hopes for – and all those hopes are based on the jobs and revenue from the Reeves County Detention Center.

Not much has changed in Pecos since the mid-1980s when the county judge latched on the idea of tying the community’s future to America’s hardening criminal justice system and booming prison industry. Reeves County was the first Texas to tap municipal revenue bonds to build a prison with the express intent of making money.

There have been financial ups and downs – worst of all when the third expansion in 2003 to its prison complex lay unoccupied for nearly two years – but, as the county judge had predicted, imprisonment is a growth industry – a bubble pumped up by a never-ending flow of per diem payments from the government. A speculative venture, no doubt, but one backed by the trust that our government will keep producing streams of inmates that it must outsource (since it is no longer building prisons or detention centers of its own).

No one here questions -- publicly at least -- the conventional wisdom that the Reeves County Detention Center has been good for Pecos and Reeves County. Now, 25 years after the prison opened, the people of Pecos still believe that their future is inextricably linked to the 485-acre prison that spreads out on the edge of town.

Phantom Residents

For the past three decades Reeves County has been losing population. At the onset of the 1980s about 18,000 people made their homes here. By the 2000 census there were some five thousand fewer residents. Over the past decade the county has lost another 16% of its population – dropping to 11,062 inhabitants in 2008.

Yet even those numbers mask the actual outmigration from Pecos and the 2,642 sq.-mile Reeves County. Beginning in 1987 the federal government began shipping hundreds and later thousands of men into Pecos. Today, there are some 3,500 mostly Mexican men who reside in the Reeves County Detention Center on the edge of town.

Entering Pecos a highway sign boasts that the town has 9,000 residents. That’s true, according to census figures, but more than a third of them aren’t legal residents. They are what the Department of Homeland Security calls “criminal aliens,” who, after serving their sentences at the county-owned, privately operated prison, will be removed from the county -- and from the country.

While the precincts in Reeves County don’t count the inmate population, the congressional and state legislative districts do. The Prison Policy Institute, the Massachusetts-based prison-reform institute that opposes what it calls “prison-based gerrymandering,” says the practice violates the constitutional principle of “One person, One vote.”

The politicians who represent Reeves County – U.S. Congressman Francisco Canseco, Texas State Senator Carlos Uresti (District 19) and Texas State Representative Pete Gallego – benefit from these phantom residents. According to the Prison Policy Institute, “When legislators claim people incarcerated in their districts are legitimate constituents, they award people who live close to the prison more of a say in government than everybody else.”

Since 2001 State Representative Harold Dutton, a Houston Democrat, has unsuccessfully championed legislation that would count state inmates from the communities they came from instead of where they are jailed. In 2009, Dutton’s proposal failed to make it out of committee, but he intends to reintroduce the measure this year after the full census results are published.

According to a Texas Tribune article about inmate counts in political representation, the number of inmates in the state’s prison system alone is larger than the size of Dutton’s House district.

The Prison Policy Institute advocates two national solutions to the problem:

* “Ideally, the U.S. Census Bureau would change where it counts incarcerated people. They should be counted as residents of their home — not prison — addresses. There is no time for that in 2010, but Texas should ask the Census Bureau for this change for 2020.

* “After the 2010 Census, the state and its local governments should, to the degree possible, count incarcerated people as residents of their home communities for redistricting purposes. Where that is not feasible, incarcerated people should be treated as providing unknown addresses instead of being used to pad the legislative districts that contain prisons.”

Institute director Peter Wagner observes that the practice of including inmates in electoral districts actually violates existing state law. The Texas Election Code defines “residence” as “domicile, that is, one's home and fixed place of habitation to which one intends to return after any temporary absence.... A person who is an inmate in a penal institution… does not, while an inmate, acquire residence at the place where the institution is located.”

Three states -- Delaware, Maryland, and New York -- have recently passed laws against prison-based gerrymandering. As the Prison Policy Institute notes, the New York Times hailed the New York law in an editorial declaring that ending prison-based gerrymandering will bring benefits to all, and calling for the new law to be emulated around the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment